Most cyberattacks are sneaky. They’re difficult to spot until the game is up, because attackers don’t want their victims to know they are under attack. There are a couple of reasons for this. Attackers want to go undetected until they have what they came for, such as sufficient level of access to launch a ransomware attack. In other cases, it’s better for the attacker that the victim never knows they’ve been hacked in the first place.

Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks are the opposite of this: They’re noisy, obvious, and incredibly destructive. So, what exactly is a DDoS?

DoS and DDoS attack definition

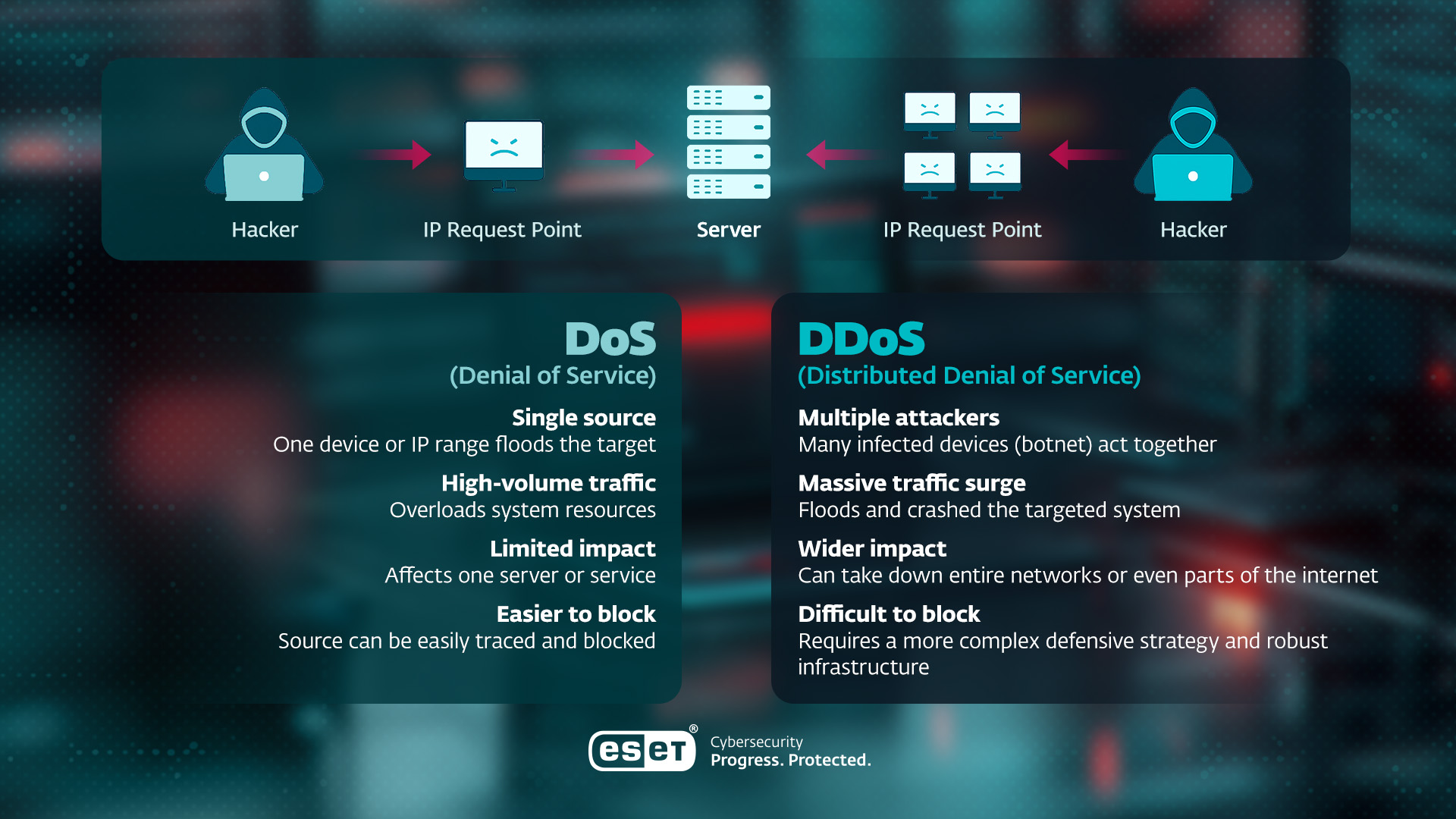

Let’s start with explaining a plain old Denial of Service (DoS), which is an attack that makes a service provided by a computer or other network resource (for example, a storage array, router, server or the entire network itself) unavailable to users by repeatedly directing high volumes of traffic at it and effectively overwhelming the service with garbage requests. The most popular target of DoS attacks is web servers.

DoS attacks can take the form of sheer volume, lots of queries containing invalid data or requests that come from illegitimate IP addresses. One way to think of it is to imagine a call center: if there are 20 lines and 20 people answering them, once the first 20 calls are taking place, other callers will hear a busy tone and an automated message. Another is to think of the network as a road system: send too many vehicles, fill all the lanes, even have some of them break down, and the traffic will stop. A DoS attack will look different to users, but the end result is the same: errors, delays and failures.

Compared to that, Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, as the name suggests, do the same thing but use vast number of different devices to send traffic to the target network or device. Often the “attacking” devices have been compromised using malware and turned into a network of devices that can be directed to send traffic to victims as a unified mass.

DDoS and DoS attacks don’t necessarily target a specific weak point. Instead, they attempt to reach the maximum capacity of any link in the chain. It might be the network itself that collapses, or it could be the processing, disk storage or memory of any one of a number of devices or services at the target. In some cases, it could be the bandwidth itself – Internet Service Providers tend to set a quota for the volume of web or internet traffic their customers use.

Regardless of this, of course, the purpose of these attacks is to deny service to users, be it employees, customers, or other users. The result is business disruption and loss of availability.

Why DDoS changed the game

Distributed Denial of Service attacks build on the idea of using distributed force – a botnet – mostly because it was fairly straightforward to block connection requests from a single network or device, and relatively easy to track back to the source. Because the traffic comes from hundreds, if not thousands, of legitimate internet connected devices, redirecting or sink-holing malicious traffic doesn’t work.

Botnets were originally conceived as benign tools: a way of building distributed computing capacity, or a way to crawl websites without using up huge amounts of bandwidth. For example, the Carna botnet was (according to its anonymous creator, at least) intended to map the use of IPV4 addresses around the world. Unfortunately, Carna achieved this feat with the help of any internet-connected devices it could access that either had no admin password, or a default username and password.

This innovation did not go unnoticed by attackers – or for that matter, a few vigilantes.

It's not just about malware-ridden PCs

It’s not just compromised computers that are used to build those botnets used for DDoS attacks. As the number of different types of smart devices connected to the internet grows, so does the risk.

The Internet of Things (IoT) contains millions of smaller devices that are typically not secure by design and – unlike PCs or smartphones – don’t have the resources to run security programs to protect themselves. Therefore they are a great target for cybercriminals and can often be compromised at scale.

In other words, a DDoS attack will very often involve herd of zombie routers, IP cameras, but also lightbulbs, fridges, and washing machines connected to the internet.

Those vigilantes mentioned earlier? Following the discovery of Carna in 2012, Linux.Wifatch, discovered in 2014 and also known as REINCARNA, attempted to build and use a botnet to patch insecure devices, logging into devices with weak credentials, cleaning out malware that had already found its way in, and disabling Telnet on the way out to prevent easy reinfection. It’s an unusual piece of malware in that its intentions appear to have been benevolent.

But Botnets are more likely to be used as a means to execute DDoS attacks. Mirai, one of the highest-profile IoT DDoS botnets, was first detected in 2016, and copycats continue to harness poorly-secured internet-connected IoT devices such as security cameras and home broadband routers. The source code for Mirai was made openly available in 2016, which has led to further development by adversaries and incorporation into a number of hacking tools.

The rise of Botnets and DDoS-as-a-Service

Attack groups have also changed DDoS into dark web services and made them available for hire, or, in the case of Booters, made botnets available to anyone whatever their motivation. The difference between a Booter and a Stresser, a (usually) legitimate commercial service used by companies to stress-test their own networks, is wafer thin, and the line is often intentionally blurred by unethical or criminal groups.

A short history of DDoS attacks

Arguably the earliest DDoS attack was the Panix Attack in 1996, which targeted early Internet Service Provider (ISP) Panix, and resulted in both days of downtime for the New York-based ISP, and subsequent loss of service to its customers. It also resulted in a spate of copycat attacks in the following year on other ISPs. The complexity and volume of attacks has only increased in following years, eating up more and more bandwidth; an attack on Amazon Web Services in 2020 was considered remarkable because it hit a peak volume of traffic at 2.3 terabits per second – the equivalent of half of British Telecom’s network traffic in a day at that point. Five years later, in May 2025, Cloudflare’s systems autonomously blocked an attack that peaked at 7.3 terabits per second. Not long after, in mid-November 2025, a 15.72 Tbps attack was detected by Microsoft DDOS Protection. The Microsoft blog covering this explicitly linked the increase in bandwidth to an increase in consumer bandwidth thanks to Fiber-to-the-Home and increasingly numerous and powerful IoT devices.

Why do DDoS attacks happen?

Attackers want to disable access to services for all kinds of reasons. In the past, disgruntled former employees, hacktivists, and trolls have used DoS and DDoS attacks to disrupt services and stop others from using them, but hackers use DDoS to distract defenders, break into services, and hold organizations to ransom. Nation States also use DDoS to disrupt the systems, social services and defense capabilities of adversaries.

Which organizations are more likely to suffer from DDoS attacks?

Luckily, there’s an open-source measurement tool that is designed to protect organizations from attacks, and it keeps records. The DDoS Resiliency Score currently shows financial services businesses, energy providers, government and public sector organizations, telecoms and internet providers, gaming and gambling companies, and software and SaaS vendors as being at higher risk of disruption by DDoS attacks. All of these organizations will suffer in the event of network downtime for different reasons.

Types of DDoS attacks

Different attacks work at different layers of the OSI network model, which gives a framework to the different levels – or layers – that make up a network. If you’re unfamiliar with this, then it’s worth spending a little time reading about it to understand how the different types of attacks focus on overwhelming different aspects of the network level they attack.

1. Layer 7 DDoS attacks

The most common attack, and the one most noticeable to users, is the Layer 7 DDoS Attack. OSI Layer 7, often referred to as the Application Layer, is where applications can access network services – think things like web servers and other applications that actual users interact with. In many L7 attacks, the malicious actor will try to overwhelm the target’s web server with as many HTTP requests as possible – what’s referred to as an HTTP Flood. In plain language, the attacker is effectively requesting to view a huge number of web pages similar to millions of users trying to browse the same website all at once, continuously refreshing their browser. As we’ll see later, this can also happen for legitimate reasons, and it’s a documented internet phenomenon.

Another example, and one that’s becoming anecdotally more prevalent, is directed at email services, either for individuals or an organization. At a personal level, users may find their inbox flooded with thousands of emails, and often this provides a smokescreen for hiding password reset and suspicious login alert that would show attackers trying to break into a victim’s account.

2. Protocol attacks

Protocol attacks are aimed at network equipment rather than applications, and target weak spots at Layer 3 (the Network Layer) and Layer 4 (the Transport Layer) of the OSI model. If you’re familiar with the OSI model, you’ll know that this approach is aimed at L3 and L4 protocols like TCP/IP. As an example, an attacker could initiate a SYN Flood attack which capitalizes on the three-way handshake on a TCP connection. This takes the form of a computer sending a SYN packet to the server to open a request. The server replies with a SYN/ACK packet to agree to the connection, opens a port, and the computer on the other end replies with an ACK packet to confirm and make the connection. In a SYN Flood attack, the attacker sends repeated connection requests in the form of a SYN packet. The target server then responds with SYN/ACK and opens a port for connection once it receives an ACK packet – which never arrives. Normally, servers close the port after a certain amount of time, but if enough SYN packets are sent by an attacker, the server is overwhelmed and stops responding to requests.

3. Volumetric attacks

The third type of DDoS attack is the Volumetric attack. This aims to flood the target’s network with traffic and data requests to overwhelm the network’s bandwidth and ability to process requests. As with application layer attacks, certain types of requests from an attacking force use very little in the way of attackers’ resources, but are costly for the target to reply to; one example is DNS query requests. Another is to use UDP (User Datagram Protocol) to flood the target’s servers with IP requests that don’t specify a destination or intended application. In all cases, this results in a server that cannot handle the number of requests that are sent its way, even if they were legitimate in the first place.

DDoS – or overwhelming legitimate traffic?

It’s worth noting that one of the most noticeable DDoS-like incidents to the average internet user is actually benign and is referred to as the Reddit Hug of Death or (if you have a few gray hairs) the Slashdot effect. This is when a website with large number of users links to a website which is in turn visited by an unexpectedly huge number of internet users, overwhelming the backend infrastructure.

While many commercial websites can handle the capacity, a service run by an individual or small business can suffer a downtime. The traffic itself is the result of thousands of curious individuals and is not intended to deny service, but ends up doing so due to that page’s popularity. One example of this is documented by Ibrahim Diallo who used his previous experience of watching his self-hosted blog collapse as a result of an article he wrote going viral to track and document the next traffic tsunami as a result of one of his stories reaching the front page of Hacker News.

Another is the Canadian government’s immigration page which was largely unreachable during the 2016 US Presidential election vote. Unexpectedly high traffic caused the page to become unreachable.

What does a DDoS attack look like?

Network administrators at your workplace or at your home ISP will have plenty of tools and training in place to notice a DDoS attack. Signals include sudden spikes in network traffic, either at unusual hours or on a regular basis, large volumes coming from a single IP range, or sudden increases in traffic to specific devices or resources. The problem is that some of these telltales are also symptoms of general internet behavior, so it’s easy to jump to the erroneous conclusion that a DDoS attack is under way when it might just be someone downloading a high-resolution movie from a streaming service on your office’s shaky WiFi connection.

Notable DDoS incidents

We’ve already mentioned Mirai and the AWS attack that caused the highest traffic rate seen at the time. An attack against Microsoft Azure, which alongside AWS and Google Cloud Platform is one of the three largest cloud providers in the world, hit a peak of 3.47 terabits per second in November 2021.

Other notable attacks include the Dyn DNS attack in October 2016 targeting Dyn, a service provider for several notable internet resources and applications, including Twitter, Airbnb, and Spotify. Another attack in 2018 targeted GitHub with an attack peaking at 1.35 terabits per second into Github’s infrastructure. In this case, the adversaries misused Memcached, a popular open source distributed caching system, to amplify the power of their attack.

Another form of DDoS attack is also notable: one executed for political ends. From Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea through to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Ukraine’s public services, telecoms, energy, media, financial, business, and non-profit sectors were heavily targeted by cyber attacks, including DDoS attacks. The attackers themselves were also heavily distributed, with groups aligned to Russia outsourcing some of the attacks to criminal groups who were rewarded with cryptocurrency for successful attacks.

Defenses against DDoS attack

There are plenty of tools and services available to mitigate DDoS attacks, but the catch is that none address all the potential avenues for attack, and attackers continue to develop new techniques and harness emerging legitimate services and technologies to enhance their effectiveness.

The challenge is that DDoS attacks by their very nature make it difficult to tackle the root cause, even if the symptoms can be treated with greater or lesser effectiveness.

Cloud services such as AWS, Azure, and GCP are often targets of attacks, but also provide services to protect their customers from overwhelming hostile traffic. AWS Shield and Microsoft Azure DDoS can both be used to protect their respective customers.

Some more traditional on-premise capabilities are still surprisingly effective. Web Application Firewalls (WAFs) defend against application layer attacks to some extent. Built in rate-limiting, traffic filter and ingress controls can blunt the edge of an attack, albeit sometimes at the risk of denying legitimate traffic. At a more architectural level, redundant DNS provisions, distributed data centers and modern network architectures engineered for resiliency can mitigate the effects.

Specialized DDoS protection, provided by many large service providers, Telecoms operators, Internet Service Providers, and Managed Services Providers, can also take away the edge of DDoS attacks. Cloudflare, Akamai, and other content delivery networks provide extra network capacity to swallow anomalous bandwidth spikes.

ISPs and Law Enforcement Agencies (LEAs) can make valuable partners during an attack, helping identify and block malicious traffic and, ultimately, identify and dismantle botnets.

Contacting the National Cyber Security Centers or similar organizations in the countries where you do business can also yield useful sources of insight and expertise, and can also help with introductions to relevant LEAs and industry experts to help with mitigation.

Finally, proper incident response planning and crisis drills are utterly worthwhile, providing your team and partners with the information and guidance to know what to do and when in the event of an attack.

What the future holds for DDoS defense

As with many cyber security areas, DDoS prevention and defense is a continuing cat and mouse game, with both defenders and attackers constantly innovating. As such, it pays to build resilience within your organization, team, and allied technology partners, rather than fixate on a mythical silver bullet that will solve the problem once and for all: if one thing is certain, it is that various types of Denial of Service attacks are not going anywhere, and defenses will have to evolve to match attackers’ new tricks.

With this challenge in mind, it’s worth considering what makes a resilient approach to defending against DDoS. Reactive defense simply won’t do. Instead, organizations need to look at defense in depth, covering as many avenues and attack vectors as possible with the tools and services to hand, conducting proactive monitoring, and engaging in regular incident planning as attacker tactics and tools evolve.