What is social engineering?

Cybersecurity can be very hi-tech. But at its heart, it’s about people. It is people attacking people – usually to steal data or generate profit. And one of the most popular ways of doing so is through social engineering. Fundamentally, this is a technique threat actors use to manipulate their victims into doing their bidding – which usually means unwittingly sharing credentials or installing malware.

Why is social engineering so successful? Because humans are fallible creatures, and we’re programmed to believe the stories others tell us – especially if those people appear to be in positions of authority. It requires neither malware nor sophisticated exploits. That makes attacks both cheaper to launch and less likely to set off any alarms. And with AI, threat actors have a powerful new tool to help them.

Let’s take a closer look at what social engineering is, how it works, and how to stop it.

How social engineering works

The “attack cycle” goes something like this:

- Reconnaissance: Gathering information on the victim in order to personalize the attack and increase its chances of success. Details can be found on social media (especially LinkedIn) and corporate sites, or sourced from breach data or open source intelligence (OSINT) tools.

- Planning: Choosing the most credible channel (e.g. email, SMS, phone, QR code, social media DM, or in person) and creating a believable “hook” (e.g. urgency, reward, fear, authority etc.)

- Exploitation: The victim buys the line they’ve been spun, and clicks on a malicious link, opens a booby-trapped attachment, agrees to transfer money, signs in to a fake login page/box, or verbally shares personal details

- Escape: The attacker steals money or logins, or deploys malware.

- Response: The organization detects the issue and begins remediation.

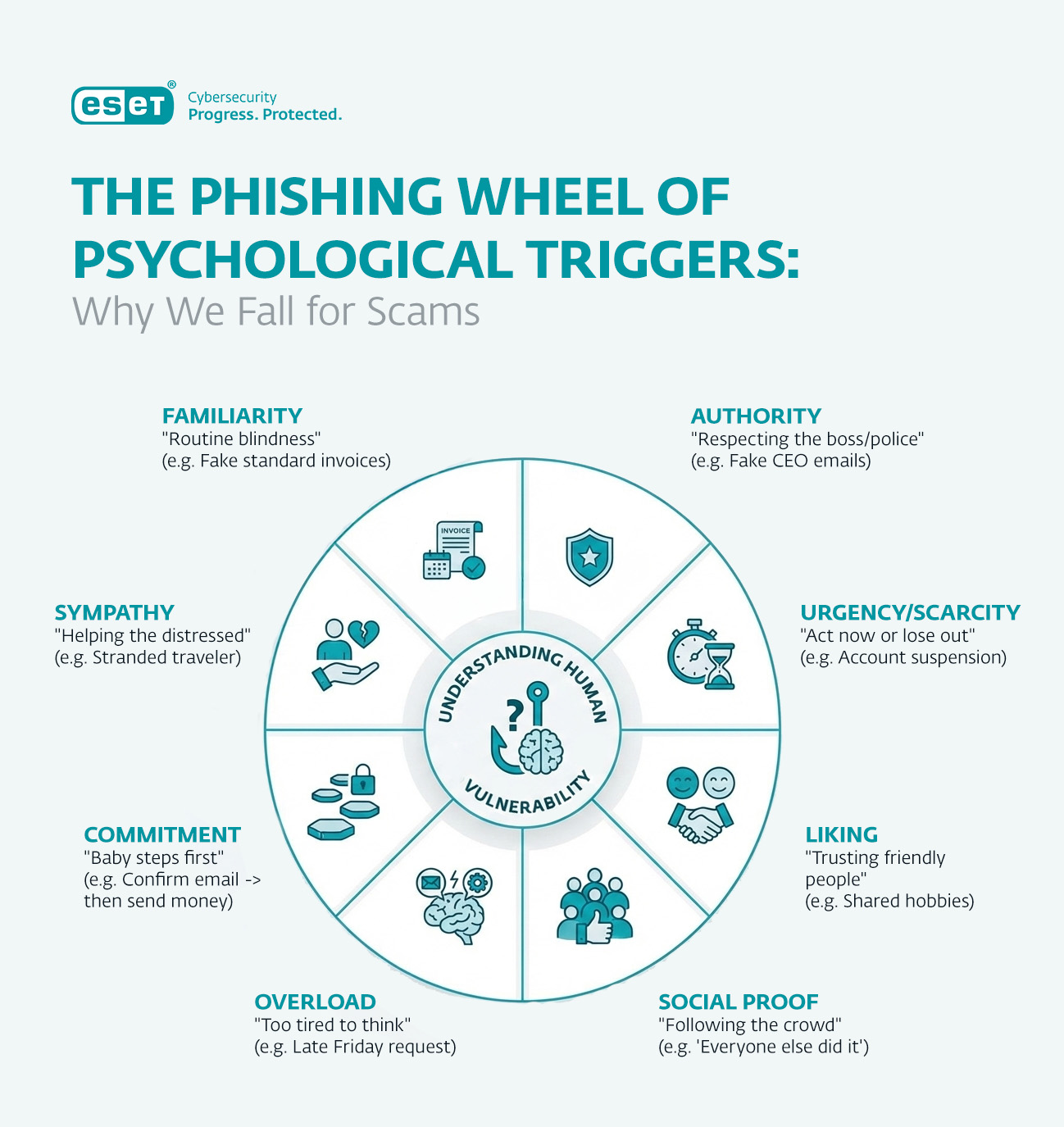

The psychology behind social engineering

At its most basic, social engineering is a con trick. But we can dig deeper, using Cialdini’s Principles of Persuasion: six rules that explain how to influence human behavior.

Authority: People are more likely to follow the orders of perceived leaders, which is why social engineers usually impersonate this type of figure (e.g. a representative from a bank/tech company/government office/C-suite).

Urgency/scarcity: People are more likely to do what you say when pressured into making quick decisions, and/or told that if they don’t, they will miss out on something. Hence phishing lures claiming an account will deactivate in 24 hours if the user doesn’t act, for example.

Reciprocity: Individuals often feel obligated to return a favor. So emails may contain a free ‘gift’ and then ask the recipient to sign up to something.

Consistency: People try to remain consistent with previous statements and actions. So if a victim agrees to a threat actor request the first time, they will be more likely to do so the second time they ask, even if it is a bigger request.

Social proof: People are more likely to follow a recommended course of action if told that their peers have already done so. A threat actor might therefore say most people in the organization have already clicked through on a link in order to ‘confirm their details.’

Liking: People are more likely to say “yes” to someone they like, so social engineers go out of their way to build rapport.

What do social engineering attacks look like today?

Not all social engineering attacks follow exactly the same pattern. It’s the variation of techniques that can often catch out victims.

Classic attacks

Among the most basic types of social engineering are:

- Phishing – Deceptive emails designed to trick the user into clicking through to a phishing page, logging into a fake portal, or initiating a malicious download

- Spear-phishing – A more personalized version of the above, usually featuring specific information on the victim designed to persuade them the message is legitimate

- Whaling – A high-impact spear-phishing attack aimed at executives

- Smishing – SMS-based phishing, usually containing a malicious link

- Vishing – Voice-based phishing where the attacker impersonates someone in authority

- Pretexting – Similar to spear-phishing, but relies on fabricating a convincing scenario to build trust with the victim. It is often used in BEC attacks

- Baiting – Luring the victim into clicking through or sharing sensitive information with the promise of special offers, rewards or prizes

- Quid Pro Quo – An attacker offers a fake product/service in return for credentials/click throughs etc.

- Watering hole attacks – Compromising sites that victims frequently visit, so that they will unwittingly infect their machine next time they visit

- Shoulder surfing – Observing a victim’s credentials/PIN/personal info in public spaces

Advanced attacks

More recently, as corporate security training programs have improved employee awareness, threat actors have begun experimenting with new ways to trick their victims:

- Business Email Compromise (BEC) – No malware, just trust exploitation and payment redirection, using pretexting techniques. The social engineer usually impersonates either a C-suite exec or a known supplier requesting urgent payment/transfer of funds

- MFA fatigue (push bombing) – The adversary sends a victim repeated MFA prompts until the user finally approves

- Deepfake video/audio impersonation – AI‑generated voice/video of executives, usually deployed in BEC attacks

- Consent phishing (malicious OAuth apps) – Attackers trick victims into granting malicious applications access to cloud-based data, by impersonating a legitimate service/app and using a fake consent screen

- Quishing (QR code phishing) – Malicious QR codes placed on signs and in public spaces (or in emails) take users to phishing sites or directly download malware

- ClickFix – A relatively new way to deliver malware while bypassing security filters. Users are first lured to a page by a phishing message/malicious ad/compromised site. Then they are presented with a fake alert which tricks them into performing a task in order to fix a temporary ‘glitch’. They are encouraged to copy and paste in order to do so. In fact, they are unwittingly running malicious commands directly in the Windows Run dialog box

- ClickFix variants – These include FileFix (copy/pasting into the Windows File Explorer address bar); ConsentFix (stealing OAuth tokens); BSOD (using fake Windows crash screens + ‘troubleshooter’ box); and CrashFix (inducing a real crash to trick the user into copy/pasting malware)

- Long‑con scams (pig butchering/romance scam) – The victim is groomed by a threat actor, often via dating site. Once they have won their trust, the scammer will suggest they invest in a crypto-investment fraud scheme

- Sextortion – Victims receive an unsolicited message claiming the sender has videoed them via their webcam in a compromising position, and will send the video to all their contacts unless a ransom is paid. Usually, the message contains some real information (e.g., email address) harvested from a historic breach. In a more worrying variation, the blackmailer scrapes a video/photo of the victim from their social media account and applies deepfake tools to nudify them. They threaten to share unless a fee is paid. In some cases, the victim may willingly share nude photos of themselves with what turn out to be ‘catfish’ accounts, before being blackmailed

Social engineering in the wild: real-world examples

Social engineering can take a huge financial and reputational toll on victim organizations and lead to an exodus of customers. Here are a few examples:

Bybit crypto heist (2025)

North Korean threat actors stole $1.4bn from the cryptocurrency exchange in the largest ever theft of its type. It was a multi-stage attack that began by targeting a developer at Safe{Wallet} – a platform used by Bybit. They tricked the dev into installing a malicious Docker Python project, which granted them access to the victim’s workstation.

MGM Resorts attack (2023)

Attackers gathered employee info from LinkedIn, called the helpdesk, impersonated staff, and gained access. The result: ransomware, downtime, service outages, and tens of millions in losses.

$25M Deepfake CFO video call (2024)

A finance staff member joined a real-time deepfake video call with someone appearing to be their CFO. They were instructed to make a confidential transfer. The attackers used AI-powered video and voice to assume the CFO’s identity.

M&S and Co-op Group ransomware (2025)

It’s believed that both of these UK retailers were targeted by the same group (Scattered Spider), which used a similar modus operandi to the MGM attack. A threat actor called the outsourced IT helpdesk impersonating an employee and was able to get their password reset, enabling access. The attacks were estimated to have cost up to £440m, with M&S unable to take online orders for weeks.

How phishing impacts consumers

Social engineering is not only a business-focused phenomenon. Threats like sextortion, ClickFix, and romance/investment scams are often, if not always, targeted at individuals. The end goal for the attacker is to obtain personal/financial information from the victim, to install malware, or to blackmail/trick them into handing over money. The financial and mental health impact can be significant.

Not all attacks are sophisticated. In fact, threat actors will usually focus on exploiting psychological vulnerabilities rather than developing anything technically sophisticated. Messages could be sent via email, text, messaging app, or social media. They’ll typically use some of the “classic” attack types listed above.

Key Red Flags

Since social engineering relies on behavioral decisions, recognizing red flags is paramount.

Red Flags to Watch Out For:

- Over-Protesting Innocence: If someone repeatedly claims, "I'm not a scam artist," they probably are.

- Demands for Trust: Trust should be earned; beware if a person you don't know keeps claiming you must trust them.

- Unusual Profiles: Be cautious if a new contact has nothing in common with you, or if a known acquaintance suddenly creates a new social media profile.

- Panic Situations: If someone contacts you in a panic (via Messenger or email) asking for urgent help, contact them through a different mode of operation (e.g., call them if they texted you).

- Flawed Language: While AI is improving grammar, subtle cues, such as translated phrases that sound unnatural in English, can indicate a scam.

- Requests for Secrecy: If someone pressures you to not tell anyone else—your boss, partner, bank, or IT department—it’s a major sign of manipulation. Legitimate organizations rarely ask you to keep requests secret.

- Inconsistent Stories or Shifting Details: If the person changes their explanation, behaves evasively, or contradicts themselves when questioned, it’s often a sign of a social-engineering script falling apart.

- Unusual Attachments or Links: Unexpected files, strange link-preview text, or URLs that don’t match the claimed destination are common attack vectors.

How to defend against social engineering

For businesses, the impact of social engineering can be devastating – enabling threat actors to gain instant access to privileged corporate resources. It could be the first stage in a damaging ransomware or cyber-espionage attack, or BEC transfer heist. Either way, significant financial, reputational and compliance damage can follow.

To mitigate the risks associated with social engineering, consider people, process and technology:

People: the human defense layer

- Regular, ongoing security awareness training, focusing on emotional triggers, not spelling mistakes

- Multi-channel simulated phishing exercises (email, SMS, voice, QR)

- Creating a culture that rewards fast reporting – even if individuals make mistakes

Process: controls around high-risk decisions

- Out-of-band verification for payments above specific limit and sensitive data

- Segregation of duties for financial operations

- Strong onboarding/offboarding and privilege management

- Identity verification for helpdesk password resets

- Clear, tested incident response playbooks

Technology: security that limits damage

- Email security to block phishing and impersonation

- Endpoint protection and sandboxing for safe attachment analysis

- Phishing-resistant MFA (e.g., FIDO2 security keys)

- Access monitoring (anomaly detection to spot suspicious activity)

- XDR/MDR for threat detection and response

- URL filtering to block malicious websites even after a click

Consider the above as part of a Zero Trust approach to security in which you trust no one, and verify all users/devices continuously according to risk.

Expert tips & insights

„Social engineering works because it exploits the gap between our taught security systems and our deeply ingrained social instincts. The same impulses that make us trusting is exactly what threat actors take advantage of, and it works well.

The most effective defense isn’t just zero trust; it’s about making yourself stop and question everything. When someone creates urgency or fear, that’s the cue to slow down and verify through a separate, trusted method. Verification has never been more important, and knowing how to use different channels is key.

Ironically, the tricky part is that legitimate requests can sometimes look suspicious too. Therefore, forming habits where double checking through multiple channels becomes normal (especially where rank is concerned), is important. Most social engineering attacks collapse the moment you step outside the attacker’s controlled narrative or platform which is why they work so hard to keep you in it.“

- Jake Moore, Global Security Advisor

Key Takeaways – Switch on the human firewall

Social engineering remains a favorite tactic for threat actors because it works so well for them. And thanks to AI tools that can create convincing deepfake audio/video and phishing messages in perfect natural language, their odds for success are now even better.

Remember, it’s emotional and psychological manipulation that enables them to succeed, not technical skill. That’s why effective defense demands a combination of people, processes, and technology. Your strongest weapon is your people. If they suspect a social engineering attempt, encourage them to slow down, confirm, and validate.

Educate and inform your employees properly (and continuously) and you will have a formidable first line of cyber defense.

ESET's multi-layer defense

When it comes to helping your organization defend against social engineering, ESET’s value comes from its combination of technology + people.

We offer technology to block the malicious clicks (ESET Endpoint Security), and prevent infected attachments from opening (ESET LiveGuard Advanced). We offer tools to protect logins even if passwords are stolen through phishing (ESET Secure Authentication). And we have continuous monitoring for suspicious behavior, which could help to stop BEC in its tracks (ESET Inspect (XDR)). Combine these capabilities with ESET Cybersecurity Awareness Training for gamified learning, and you have a powerful multi-layered defense against social engineering.

For consumers, cybercriminals don’t just target companies – they also prey on individuals through phishing emails, fake websites, and social media scams. That’s why ESET brings the same dual-layer approach to home users through ESET HOME Security:

- Technology layer: ESET HOME Security plans include advanced protection against phishing, malicious links, and infected downloads, plus features like VPN, Safe Banking & Browsing, and Browser Privacy and Security to safeguard sensitive transactions and online activity

- Human layer: Through ESET’s consumer education resources and interactive guides, we teach users how to spot scams, avoid suspicious links, and secure their online accounts.

Together, these layers help families stay safe from social engineering attacks that could lead to identity theft or financial loss.

FAQ: Social engineering in cybersecurity

What are the four main types of social engineering?

Phishing, pretexting, baiting, and tailgating are four of the most common social engineering attack types. They rely on deception, urgency, and/or trust to manipulate people into revealing information or granting access.

How does social engineering work?

Social engineering works by exploiting human psychology – not technical flaws. Attackers use emotions like urgency, fear, and curiosity to push people into making unwise decisions such as clicking links, entering passwords, or approving transactions.

What is a simple example of social engineering?

An email sender impersonates a company executive, requesting an urgent payment. The attacker uses authority and urgency to bypass normal verification steps.

Is social engineering illegal?

Yes. Any manipulation aimed at unauthorized access, fraud, or data theft is illegal in most countries.

Can security software stop social engineering?

Security software can block malicious files and dangerous links, but it cannot stop psychological manipulation. Training, verification, and layered defenses are essential.

What is the goal of social engineering?

To trick people into taking actions that benefit the attacker – providing access, money, or sensitive information.

How do I know if I’m being socially engineered?

Look for urgency, fear, secrecy, requests to bypass policy, unknown senders, or unusual payment or login requests.