When talking about the deep web, there tends to be a lot of fearmongering, as is the trend with news in general nowadays. In truth, it’s only as nefarious as anything else. In the wrong hands, it can be used for illicit purposes such as drugs, guns, or even worse in what’s notoriously called ‘the dark web.’

Conversely, the deep web doesn’t have to be so dark, as it’s also used by whistle-blowers, journalists, and people seeking anonymity in a world where privacy is increasingly becoming a luxury. In some cases, people may even have to utilise these services to access sites which are inaccessible otherwise, e.g. utilising Facebook in Iran, Cuba, and China.

That said, when I hopped on the Tor Browser out of curiosity, I realised it only takes three clicks to find yourself in an illegal online marketplace offering all sorts of illicit substances. It’s a similar story when checking how difficult it is to purchase unlawful arms – not difficult at all.

In the same way nuclear power may be exploited differently depending on the user, it is a similar case here. Where nuclear power may be used to provide low-emission energy in mass quantities, it may also be used for ulterior purposes, such as developing nuclear weapons. The deep web can be a haven for people looking to maintain their privacy on the web in an age where this is becoming increasingly difficult, but this privacy can also be used by criminals to avoid detection by law enforcement agencies. For example, you may have seen headlines recently about a 1.4 billion credentials dump circulating online. Although this was slightly more difficult to trace, it still took under 20 minutes to locate and begin downloading the 41GB database.

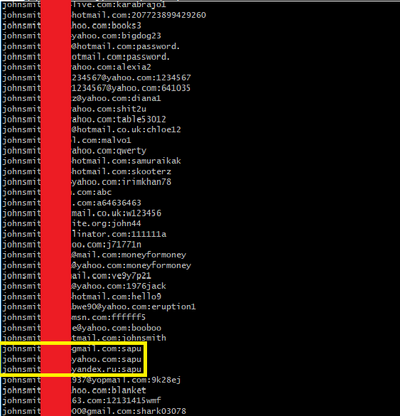

Passwords such as “password”(fifth and sixth from the top) as well as sequential number or even just repeated passwords across accounts (highlighted in yellow), are still disturbingly common.

The deep web is an area of the internet where most of our ‘cloud’ storage is, as well as many databases which are on the internet but aren’t index-able by regular web search crawlers such as Google, Yahoo, or Bing. The ‘covertness’ of certain services such as databases hosting log-in details to Facebook or PayPal is obviously a positive thing as it means attackers wouldn’t even know which IP address to target as they have no index of it. This Infographic by CNN Money provides an abstract view of the world wide web in terms of visibility, shown by depth.

There are different types of sites on the deep web. The contents of research databases, such as EBSCOhost, are part of the deep web despite being easily accessible, and sometimes free of charge. On the other hand, there are sites which require a specific protocol to be accessed; these are generally sites with a .onion domain. On this domain, sites can be as varied as a .onion mirror of Facebook, to a site advertising for-hire hitmen. Chances are, if you’ve heard of ‘the dark web’, this is the side you’ve heard of where a range of illegal activities flourish under the veil of anonymity, supported by cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin.

What are .onion addresses anyway?

… And why can’t we access them in our usual browser? Whereas the typical website utilises a domain which may be resolved using one of a list of DNS servers which web browsers are capable of contacting, a .onion website is not accessed by translating domain names (e.g. google.com) into their corresponding IP addresses (216.58.201.110). Instead, the process is much more complicated, as rather than directly connecting to the server hosting the website through a centralised DNS server, the browser undergoes multiple steps.

Beginning with the domain of the site, names are automatically generated - resulting in domains such as http://3g2upl4pq6kufc4m.onion/ for duckduckg - based off an asymmetric encryption. Next domains have to be placed on a specified database similar to the olden days of the internet, before there were web crawlers which could index sites on our behalf. A user would then find the domain on the index and set up a connection to a relay point and a rendezvous point. The server is already connected in a circle to the relay points and therefore receives the message the user sent, and a connection is established.

If you’ve ever watched the HBO show Silicon Valley where they strive to create a decentralised internet, much of the deep web sits on precisely that. The Tor network is a decentralised network which is partially what allows it to be such an attractive privacy proposition. If you wish to connect to a site, after having gone through the steps mentioned above, your tor client will have established a Tor circuit, (a connection going through a series of peers), which then leads to a Rendezvous Point (RP), and finally to your requested site.

The issue with this concept is that it leaves it exposed to Sybil attacks. If an attacker casts a wide enough net - by introducing thousands of nodes into the tor network for example - some of those nodes are bound to become either entry or exit nodes. Although since data packets are encrypted, if nodes in the middle of the circuit are compromised, they won’t have access to any data except for the previous and the next node in the circuit, neither of which is particularly useful in attempting to compromise the user. Due to this vulnerability, it is still recommended to utilise a reliable VPN solution in order to mitigate the risk of compromised nodes, as well as selecting your relay nodes on Tor carefully.